our inspiration

our inspiration

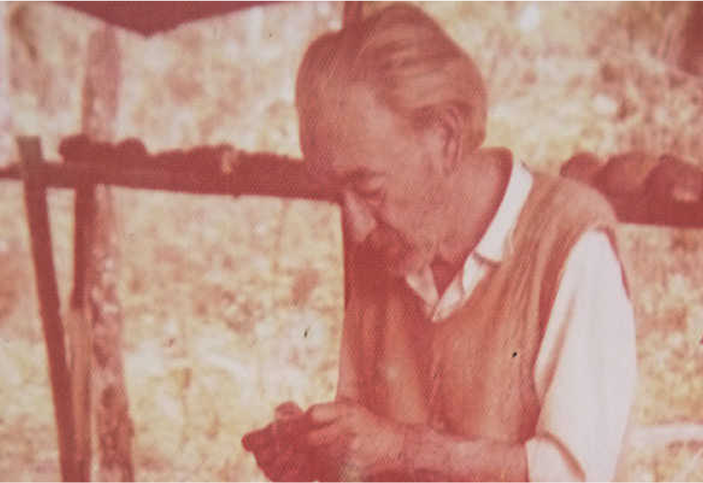

Andrés Gaspar Giai

(May 10, 1913–1977)

The protected area in which GüiráOga is located is named “Andrés Giai” in honour of this renowned naturalist.

In 1947, he became the new head of the museum’s Ornithology Section. He was looking for an opportunity to participate in expeditions to the interior of the country at the time, and this came in the form of a rare duck specimen with a sharp beak loaded with small “teeth” and a distinctive crest. Dr E. del Ponte and taxidermist A. Aiello had captured it on the eastern border of Misiones while conducting yellow fever research. Giai immediately identified it as a Brazilian merganser, a species that was virtually unknown at the time, with only three specimens in Argentine collections, and rumours of its presumed extinction.

It took little to convince the museum’s director, Agustín Riggi, of the advisability of undertaking an expedition to the then National Territory of Misiones. In 1948, with the help of the National Road Authority, which was building Route 12, Giai reached the bridge over the Aguaray Guazú stream in this almost pristine land—his first encounter with the jungle and its secrets. He learnt about the “corrección” (army ant attacks), mingled with local guides who taught him to distinguish wild bees (even by the smell of their honey), and acquired the basics of hunting in the wild. He himself became a local guide, identifying tracks and learning to trap and hunt as the locals did. His main motive was scientific research, but he also needed to feed himself, since those remote places had no stores or houses where he could obtain supplies.

He realised that the best way to explore the intricate terrain of the routes in Misiones was to navigate the streams, rowing vigorously against the current in the backwaters and dragging the boat on foot over the rocks of the rapids. The Brazilian earpod tree provided the best wood for building light yet sturdy boats. His efforts were rewarded with the discovery of new species, some of which had never been recorded in the country before.

His first pair of Brazilian mergansers had already been taxidermized when a rat, which had taken up residence in his pindó-roofed ranch, attacked one of its legs. The search for new specimens was complicated in the Aguaray Guazú, as Giai explained: “The entire forest of the Aguaraí Guazú River has already been exploited for hardwoods and, as is usually the case, the undergrowth has progressed, weaving a devilish undergrowth vegetation.”

He therefore decided to head further north, to the Urugua-í, where the forests were still virgin, and the jaguars approached the road maintenance camp to observe the intruders, and where there was no news of any explorations upriver. Píriz and Pedro Mareco, a black man who, according to rumours, “could smell animals,” were his guides. The three disappeared into the jungle for months. Left to his own devices and physical endurance, Giai was determined to capture everything. The Brazilian merganser duck was a common sight, and he was able to obtain new specimens. He no longer had to protect them from rats, but from crested eagles—such as the Black-and-white Hawk and the Ornate Hawk-eagle, natural predators of the duck—who tried to snatch the embalmed specimens from him.

He witnessed the actions of “gangs” of giant river otters chasing fish and turtles. He heard the cries and puffs of an animal that has now seems to have disappeared from Argentina. He lived alongside capybaras, deer, wild pigs (tateto and cabalí), tapirs, lowland pacas, agoutis, cougars, ocelots, guans, capuchin monkeys, and coatis—to name just a few of the species he described in his writings.

But the lack of news began to worry relatives and colleagues at the museum, and the local police had lost track of them at the road maintenance camp. Several months passed… until three bearded, very thin men emerged from the Urugua-í jungle: they had lived on bush meat, mate, and “reviro” (a local dish made of manioc flour) and brought with them a valuable cargo of new fauna specimens (including four Brazilian merganser ducks). The chronicles of their journey and the scientific results were published between 1950 and 1951 in El Hornero.

Their stories caused such enthusiasm among their colleagues at the museum that new trips began to be planned, with William Partridge and Jorge Cranwell joining them. They obtained funding to set up the “Yacú-poí” base camp (almost a “biological station”), strategically located near the now classic “Barrero Palacio”. They obtained funding to set up the “Yacú-poí” base camp (almost a “biological station”), strategically located near the now classic “Barrero Palacio” or “Palace salt lick” (barrero: name given by people in Misiones to places where animals go in search of naturally occurring salts). Perfecto Rivas, the local guide with whom Giai struck up a lasting friendship, had never seen a palace, not even in photos, but he christened the salt lick with that name because he found it “magnificent and as tall as a palace.”

Thanks to the exploits of Andrés Giai, the camp remained in operation until 1960. At times, it was populated by prestigious researchers, naturalists, and taxidermists, as well as a significant number of local guides and friends, whom Giai entertained by frequently playing the guitar.

But Andrés Giai left the scene around 1952, taking with him indelible memories. He left the jungle at the same time as his friend Perfecto Rivas, who preferred to give away his gun, with which he “had already killed twelve tigers… if there was a thirteenth, it would hunt him down.”

Giai’s new home was the northern Patagonian mountain range. He lived in Bariloche, continued bird watching, and now tracked South Andean deer. In the 1970s, he decided to rescue his articles published in old magazines and compile them into a book. That’s what he was doing when documentary filmmaker Andy Pruna met him and didn’t hesitate to include his expertise and charisma in “Once Upon a Time in the South”, a nature documentary that was a box office hit. Pruna was so pleased with Don Andrés that he proposed filming “Once Upon a Time in the North” in the Misiones of his memories.

Giai embraced the idea with enthusiasm and returned to the jungle in 1975. He visited the Iguazú Falls and stayed at the Yacuy Section of the National Park. He made his base in Puerto Esperanza. Between mate and mate, he had told his friends, “I’m going to stay in Misiones, because all the birds know me here.” But who knows what premonition led him to show up one day at Hugo Pesce’s house with the following phrase: “Here I am, I’ve come to die.”

Shortly after that, on a cold dawn, Andrés Giai (“Andresito” to his close friends), the excellent naturalist, skilled artist, brilliant taxidermist, multi-instrumentalist, this “Hudson” of the 20th century, fell silent forever. His friends buried him in the jungle.

He did not even know that many of the species he once hunted were now extinct. That a hydroelectric project would eventually flood the jungle of his adventures. He left when he was most needed: he would have been an unconditional ally in saving the jungle. A challenge that he himself instilled in us, surely without knowing it, from the pages of his book published a year after his departure, “Life of a Naturalist in Misiones.”

Andrés Giai stayed in the jungle he loved so much.